Jacob Gostanian, 127

It’s late on a Sunday night in September, and a Peace Corps Thailand Volunteer sleeps soundly in his room. Snuggled up in his blankets, the only background noise entering his ears is the buzz of the AC unit. Suddenly the PCV’s phone yells out beep, beep, beep, beep, beep, beep! Groggily he fumbles for it, shuts off the alarm, pulls it off the charger, and checks the push notifications. He rubs his eyes, heads to the bathroom, washes his hands in the sink, grabs an apple and some water from the fridge, hops back in bed and opens up his computer. It’s midnight in Thailand but on the East Coast of the US it’s 1pm on Sunday and football is just starting. The PCV has two windows open on his computer, one is the live stream of an NFL game and the second is his fantasy football team.

This PCV was me a few Sundays ago. Now, while this is not how every PCV  in Thailand lives, every PCV could live like this if they wanted to badly enough. So let’s see what we can discern from that paragraph. In that paragraph I have access to (1) running water, (2) electricity, (3) internet. Now as far as amenities go, I have a refrigerator, an air conditioner, and a functioning smartphone. Now again: Not every volunteer has all of these luxuries, but they have access. If all that mattered to you was an air conditioner, you could get an air conditioner. If all that mattered to you was WIFI, you could get WIFI. While this doesn’t necessarily help support my point of how tough it is being a volunteer in Thailand, it provides the positive half of the duality that all PCVs experience in Thailand. The other half is that we cannot afford all of these things, we have to ride our bikes everywhere (when every Thai national rides a scooter or drives a car), and we do not have the ability to accept rides from people in any form besides a seat in a car.

in Thailand lives, every PCV could live like this if they wanted to badly enough. So let’s see what we can discern from that paragraph. In that paragraph I have access to (1) running water, (2) electricity, (3) internet. Now as far as amenities go, I have a refrigerator, an air conditioner, and a functioning smartphone. Now again: Not every volunteer has all of these luxuries, but they have access. If all that mattered to you was an air conditioner, you could get an air conditioner. If all that mattered to you was WIFI, you could get WIFI. While this doesn’t necessarily help support my point of how tough it is being a volunteer in Thailand, it provides the positive half of the duality that all PCVs experience in Thailand. The other half is that we cannot afford all of these things, we have to ride our bikes everywhere (when every Thai national rides a scooter or drives a car), and we do not have the ability to accept rides from people in any form besides a seat in a car.

The gap between want and need is narrow here, and easily bridgeable by point of view. For example, from my point of view I need AC to sleep. Right or wrong, thats my point of view. The crucial part here is that in Thailand that is a need for me, but if I was living in a mud hut in Africa (or wherever the mud hut PCVs are located), I wouldn’t have electricity and therefore couldn’t have an AC – thus turning my need here in Thailand into a want in other countries.

You might be thinking: Why is this tough on Thailand PCVs? The reason this leads to trouble is just because you have access to your “Thailand needs,” doesn’t mean you have the ability to procure them. This brings us neatly into the issue of having access to the western world and its potentially detrimental effect on volunteers.

Here in Thailand, PCVs have access to the Western world – but not in the same way we are accustomed to. Here we must choose some aspects and we must give up some aspects. That choice is part of what makes service here hard. It feels like we are always giving things up because we don’t have the means to procure everything we have access to: “Do I want to buy some Western food this month because I can’t eat rice with another meal, or do I want to go visit some other PCVs?” Choices like this are real, and they bring about unhappiness and reduce our locus of control. I’m not saying that one decision does this, but many choices are compounded upon each other daily and they add up quickly as we are forced to make these types of decisions all the time.

Adding to the issue of limited access to Western tangibles, we have full access to our Western intangibles – lives and relationships via social media. With a time difference of +11-13 hours (depending on your time zone in the States) we are afforded two convenient windows to talk to friends and family at home every day. While this can be a good thing, it can also be very harmful. Maybe you wake up and chat with your friends from the States, they all went out for dinner, they say they miss you and wish you were there, then you spend all day scrolling through Facebook looking at what you view as things you’re missing out on happening back home. In the evening you’re afforded another opportunity before bed, you talk with your parents, check in, and maybe see your family pet that you left behind, stirring up a deep longing for home and its comforts. The point is that it is very easy to get stuck in your US life with internet being so readily available here in Thailand. If what we have covered so far was the extent of the issue, this article, while still making very true and valid points (in my opinion at least), would be kind of whiny. But we have not yet touched on the challenges of serving in our communities.

When it comes to life at site, PCVs in Thailand have to deal with a perfect storm of a developed governmental structure (hierarchy). There is the community’s objectives for their PCV, the Peace Corps programs goals and objectives for the PCV, the PCV’s own goals and objectives, the Thai language (one of the hardest language of any country that PCVs currently serve in), and  (as a cherry on top) the general polite nature of Thai culture and saving face. There are a few main issues that can be teased out of the above obstacles: (1) It’s hard to effectively communicate ideas and goals with Counterparts (if you even have Counterparts to work with that is). (2) Once you do find something you can do to be useful, it’s hard to cut through the red tape and actually get anything done. Back-and-forths between involved parties are tough enough to manage in your native tongue, let alone in Thai, and you never know if your talking to the right person, or if you have done everything you need to on your end (mainly because no one told you about the other thing you needed to do). (3) It’s incredibly hard to do all of this within the context of Thai culture. You can’t just bull your way through it. Everything has to be done with tact and timing, tiptoeing around the things you really want to just bluntly say. (4) You don’t know if what you’re doing really matters and will make a difference in the end, or if it is what your community really wants or needs. It’s hard to measure if a teacher is teaching better, or if a community’s youth have more life skills in just two years time. Given everything else, at the end of the day (5) Are you doing what you thought you signed up to do?

(as a cherry on top) the general polite nature of Thai culture and saving face. There are a few main issues that can be teased out of the above obstacles: (1) It’s hard to effectively communicate ideas and goals with Counterparts (if you even have Counterparts to work with that is). (2) Once you do find something you can do to be useful, it’s hard to cut through the red tape and actually get anything done. Back-and-forths between involved parties are tough enough to manage in your native tongue, let alone in Thai, and you never know if your talking to the right person, or if you have done everything you need to on your end (mainly because no one told you about the other thing you needed to do). (3) It’s incredibly hard to do all of this within the context of Thai culture. You can’t just bull your way through it. Everything has to be done with tact and timing, tiptoeing around the things you really want to just bluntly say. (4) You don’t know if what you’re doing really matters and will make a difference in the end, or if it is what your community really wants or needs. It’s hard to measure if a teacher is teaching better, or if a community’s youth have more life skills in just two years time. Given everything else, at the end of the day (5) Are you doing what you thought you signed up to do?

Doing what you thought you signed up for is the hardest thing about serving in Thailand at times. With expectations coming from every angle, it can feel like you’re just being used in a sense. It can also feel like a regular job back home: going to the office; talking to your boss; submitting reports; and then going home. It begs the question: Is this what I singed up for? Is this worth two years of my youth (sorry older volunteers, I’m just going with average PCV demographics)? For some people the answer is no, and more likely than not if the answer is no, it leads to an Early Termination (ET).

There are several types of ETs: Trainee/Volunteer Resignation, Medical Separation, Administrative Separation, and Interrupted Service. Each has the same end result of the volunteer returning stateside, and for that reason when talking about ET rate we will include them all. While there might be extenuating circumstances in some ETs, at the end of the day it is what it is and an ET is an ET.

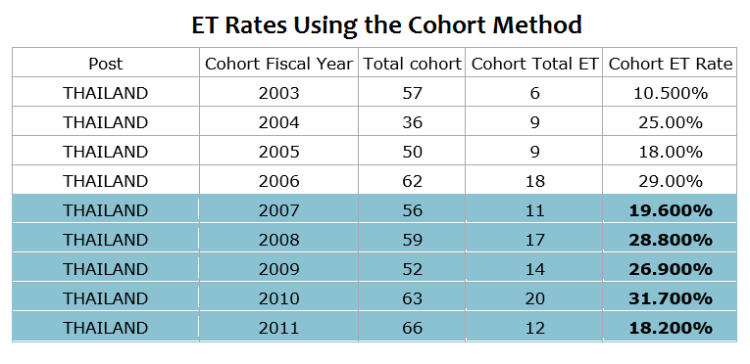

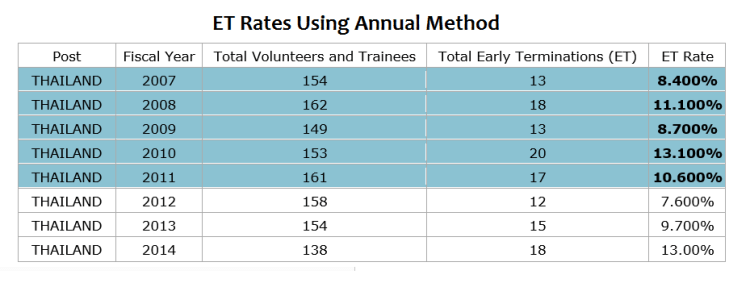

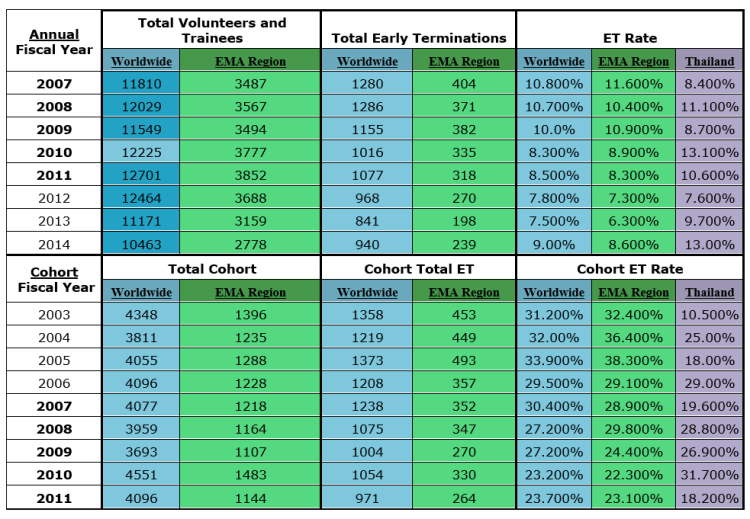

In reporting the ET rate throughout the world, the Peace Corps uses the Annual ET rate and the Cohort ET rate. The difference being that with the Annual rate you are looking at the number of volunteers (& trainees) who ET (for any reason) from October 1st of any given year to September 30th of the following year, and the Cohort rate measures the total number of people who ET’ed in a group from the start of PST to COS (Close of Service). While in the end of time the total numbers will be the same, this cross section of data cheats the number of volunteers who make it the whole 27 months. According to Peace Corps Headquarters, “To ensure accuracy, cohort rates are not calculated until at least 95% of a cohort has completed their service. This means that complete cohort rates typically cannot be calculated until 2-3 years after a cohort begins (at the end of FY 2014, when the last ET datasets were published, the FY 2011 cohort rate was the most recent available). The annual rate is designed to be a more timely complement to the cohort rate.”

My issue with the annual rate is that this method pads the initial fallout from an incoming group. During three months of the fiscal year (for Thailand at least) there are three groups of volunteers in Thailand. Example: in January, February, and March of 2015, Groups 125,126, and 127 were all active in Thailand.

Let’s take a look at what stage of service the two current groups of PCVs are in when the fiscal year starts (October first). The most recent group of volunteers (lets call them G1) is about 9.5 months into their service (a little over 1/3 of the way to service completion), the second, more tenured group of volunteers (lets call them G2), only has 7 months left in service (roughly 75% of their is service complete). It’s safe to assume the ET rate in G1 has pretty much stabilized, the herd has been thinned and aside from a few medical separations and a few miscellaneous separations those who have made it 9.5 months are here to stay. It’s also safe to say that the ET rate in G2 should pretty much be nonexistent; if you’ve made it 20 months, the list of reasons for you to ET becomes very, very short. When January rolls around and the new PCTs/eventual PCVs (let’s call them G3) get here, the total number of volunteers in the country spike up, all things being equal, by about 1/3. The ET rate of the G3 from the time they arrive until the end of fiscal year should be immensely higher that of G1 and G2. This creates a big pad in the ET rate. For example, say the total volunteers in G1 and G2 is 115 on October 1st. Let’s say 5 of them leave before the end of the fiscal year. Let’s also assume that the new group has 70 people and they lose 15 before October first. Using the Cohort method, the ET rate at the end of G3’s service would automatically be no less than 21.4% (15/70), assuming they lost no one else after October 1st. Now using the annual method the ET rate becomes 10.8% (20/185). So while this has been a rather long example it is important because now we know that the annual ETs put out by the Peace Corps don’t really hold any weight, and if you ask me this method of reporting is tantamount to cooking the books in the accounting world, and shouldn’t be allowed; or at least allowed without the addition of the Cohort rate.

Now that we have learned about how ET Rates are calculated we can get to the juicy stuff, like why does Thailand have such a high ET rate? I hate to be the bearer of bad news to my fellow Thailand PCVs, but we’re not terribly special. Our average ET rate, using either method – annual or cohort, is all over the board, albeit with a trend toward the higher side in the last few years. We are far from the top tier of ET rates by country.

Fun fact: Our Thailand resides with the Peace Corps global region called EMA, which stands for Europe, Mediterranean, and Asia.

The EMA consists of the following countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Cambodia, China, Georgia, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Macedonia, Moldova, Mongolia, Morocco, Nepal, Philippines, Romania, Thailand, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine; for a grand total of 22 countries. Now I realize that not all countries listed above are still active but if their numbers were included in any of the data sets, they got listed.

This data, and all other Global and Historical ET data can be found on the Peace Corps website.

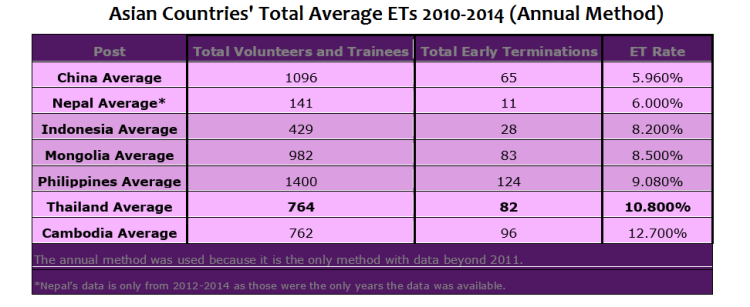

While it’s true that Thailand’s ET rate isn’t terribly out of place among the global average (I’d place us within the 1st standard deviation from the Global Average), or the regional average, if we look at just the A in EMA, we are slightly above the average. We have the second highest average ET rate over the last 5 Fiscal Years in Asia/South East Asia. This is relatively significant on some level when you take into consideration that basically all of the countries listed below have similar cultures in the sense of being largely Buddhist, and practice non-violence and tolerance.

I attribute Thailand coming in second place for ET rate among our regional neighbors to everything I have detailed in this article. While the numbers on a Global and Regional scale (EMA) point to Thailand being on par (or only slightly above average) with the rest of the globe, I believe we would be far above average in a GDP (Gross Domestic Product)-to-ET rate comparison. It was not within the scope of this article, nor did I have the time, to gather the GDP data for all Peace Corps countries and cross reference them in a meaningful manner with corresponding ET rates. Maybe next time. I do believe that if you compared those figures you would discover 1 of 2 things: either Thailand was an above average country in ET rate terms when you factor in GDP; or you might find that Thailand has similar challenges to other developed countries, and that it can be just as challenging to serve in a more developed country than an undeveloped country – which means that the idea of “Posh Corps” is a myth.

Share your thoughts